Costly COVID-19 mistakes: Pa. companies brace for second shutdown

James McGinnis

Published 6:00 AM EDT Aug 12, 2020

Editor's Note: COVID-19 killed tens of thousands in the Northeast, caused massive unemployment and wrecked the economy. In an ongoing series of stories, the USA TODAY Network Atlantic Group, 37 news sites including those in south-central Pennsylvania, examines what the government got wrong in its response to the virus, what policies eventually worked — and why we remain vulnerable if the coronavirus strikes harder in the fall.

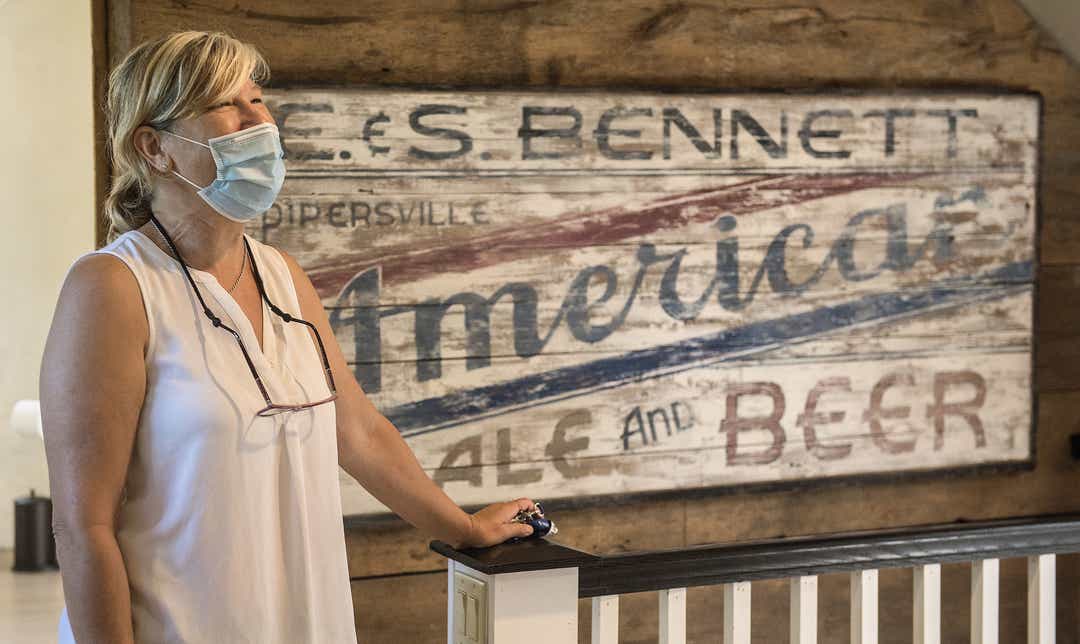

Ed and Sherri Bennett have a beautiful dream, and it may not survive the winter.

Ed is a local artist. Sherri is a public school teacher. In 2017, they opened the Galvanized America Inn and Art Gallery. A Bedminster farmhouse dating back to 1754 was converted into a bed and breakfast with an outdoor pool and sweeping views of Pennsylvania farm country.

”In March, people began canceling (reservations) even into July,” said Sherri. “Things are starting to look better, but if we’re all quarantined again, I just don’t know what that’s going to mean for us. I don’t know what we would do, if we see our dream fall apart.”

Across Pennsylvania, thousands of business owners are in the same boat. Countless questions. Few answers. Uncertainty has a chilling effect.

The region’s first brush with the pandemic knocked down hundreds of companies and left millions unemployed, if only temporarily, records show.

What failed

Business owners rarely issue a press release or publicly announce plans to close.

So, we’ll never know exactly how many companies were wiped out in the past five months, explained Gordon Denlinger, state director for the National Federal of Independent Business Owners.

"When a business owner sees bankruptcy coming, they’ll get in front of that bankruptcy,“ Denlinger said. ”Quietly, they’ll make the decision not to reopen as opposed to showing up in the numbers of bankruptcy filings.“

Hotels and accommodations will account for many of those largely unannounced closings, predicted Gene Barr, president and CEO of the Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry.

“They were the first ones taken down,” said Barr. “It’s a major hit to state and local governments because of the hotel taxes that are imposed. If those don’t come back, there’s a significant ripple throughout the economy.”

Denlinger echoed those forecasts.

“That is certainly happening,” he said. “We know it’s not a small number, but we don’t have a measurement on it.”

Some companies are required by federal law to notify the state of a business closure. The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act [WARN] covers most businesses with 100 or more employees.

Since April, state records show at least 45 business announcing plans to close and permanently layoff workers. WARN notices came from high-end restaurants in downtown Philadelphia, caterers in Johnstown, an LED lighting supplier in Bethlehem, and a QVC distribution center in Lancaster, among others.

For nine weeks, the U.S. Census Bureau has also conducted a weekly survey of small businesses, reaching more than 1 million companies with fewer than 500 employees.

In Pennsylvania, 82% of surveyed small business owners reported a significant negative impact from the pandemic. The greatest number – 41% – predicted it would take more than six months to recover.

One bright spot in the report showed small businesses that have reopened across the state in recent weeks. In April, 55% were closed. That figure dropped to 20% as of June 27, the latest available estimates from a U.S. Census Bureau Small Business Pulse Survey.

What worked

Business leaders have largely praised the federal relief package that came in mid-April.

Early on, the federal government began paying companies to retain workers and stay open. The $2 trillion CARES Act included $659 billion in payment protection program “loans,” which were “fully forgiven” after the company used the money to cover payroll, mortgages, rent or utilities.

It’s impossible to tell exactly how much PPP money was give out or tally the exact number of jobs saved. Here’s why:

The U.S. Department of Labor has held back on releasing information. The federal government said it must maintain a “balance between providing transparency ...and protecting confidential business information.”

For PPP payments exceeding $150,000, the name of the company was disclosed but not the exact amount of money the company got. Payments are categorized in amounts such as “$1 million to $2 million“ or “$5 million to $10 million.“

The rules were different for smaller applications. For payments valued at less than $150,000, the exact amount is disclosed. But, the name of the company was not released.

Also, the number of saved jobs via each payment is not based on government data. Each company self-reported an estimate of how many jobs would be saved by each payment awarded.

From what was disclosed, we can tell that companies across Pennsylvania applied for and received at least $15 billion in PPP. The vast majority of those loans – 84% – were valued at less than $150,000, according to government records.

When applying, companies in Pennsylvania said the payments would allow them to retain – collectively – some 1.8 million employees across the state. If accurate, that breaks down to about $9,000 per worker job retained during a period of approximately eight weeks.

What needs to be done for a second wave

As the crisis rolls on, business leaders are lobbying for more government support and protections from lawsuits related to the virus.

“There is clearly a need for another round of relief to give our businesses some runway,” said Denlinger. The NFIB argues the funds should go to the hardest hit industries with a proper accounting for how it will be spent.

“PPP pushed a significant amount of money out the door in a very short period of time. But there was quite clearly a delay in getting out the information about to how to apply,” said Barr.

While they argue for increased business support, corporations are also asking the government to stop federal stimulus payments to the unemployed. The CARES Act provided additional cash to some unemployed workers during the pandemic.

Denlinger described anger at some firms where the furloughed workers were receiving more money than employees who remained on the job.

"I’ve got members who say that they have more (job) openings than at any time in their history as a company,“ said Barr. ”They can’t hire people.“

Across the state, many are also concerned about potential lawsuits from both workers or customers.

Among the more high-profile cases, the Giant Eagle grocery store chain faces more than a dozen lawsuits from customers who refused to wear masks citing medical conditions.

“We’re already seeing increasing lawsuits and it’s just unbelievable,” said Barr. “We’re being told every single day that the most important thing is wearing a mask and we have people walking into stores that are not wearing a mask.”

“We need the state government to give some reasonable premises liability protections,” said Denlinger. “Simply put, if you do all the right things and you follow the CDC guidelines, you should have a shield against these lawsuits. We deserve some level of protection.”

If the state does again shutdown some businesses, the system needs to be fairer, argues the National Federation of Independent Business Owners.

“A review of the governor’s waiver process needs to occur,” Denligner said. “We had businesses open on one side of the street and closed on the other side of the street. And, they were the same type of business. It definitely seemed to benefit larger companies over your small, independent business.”

James McGinnis is a reporter for the USA Today Network in Pennsylvania.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de