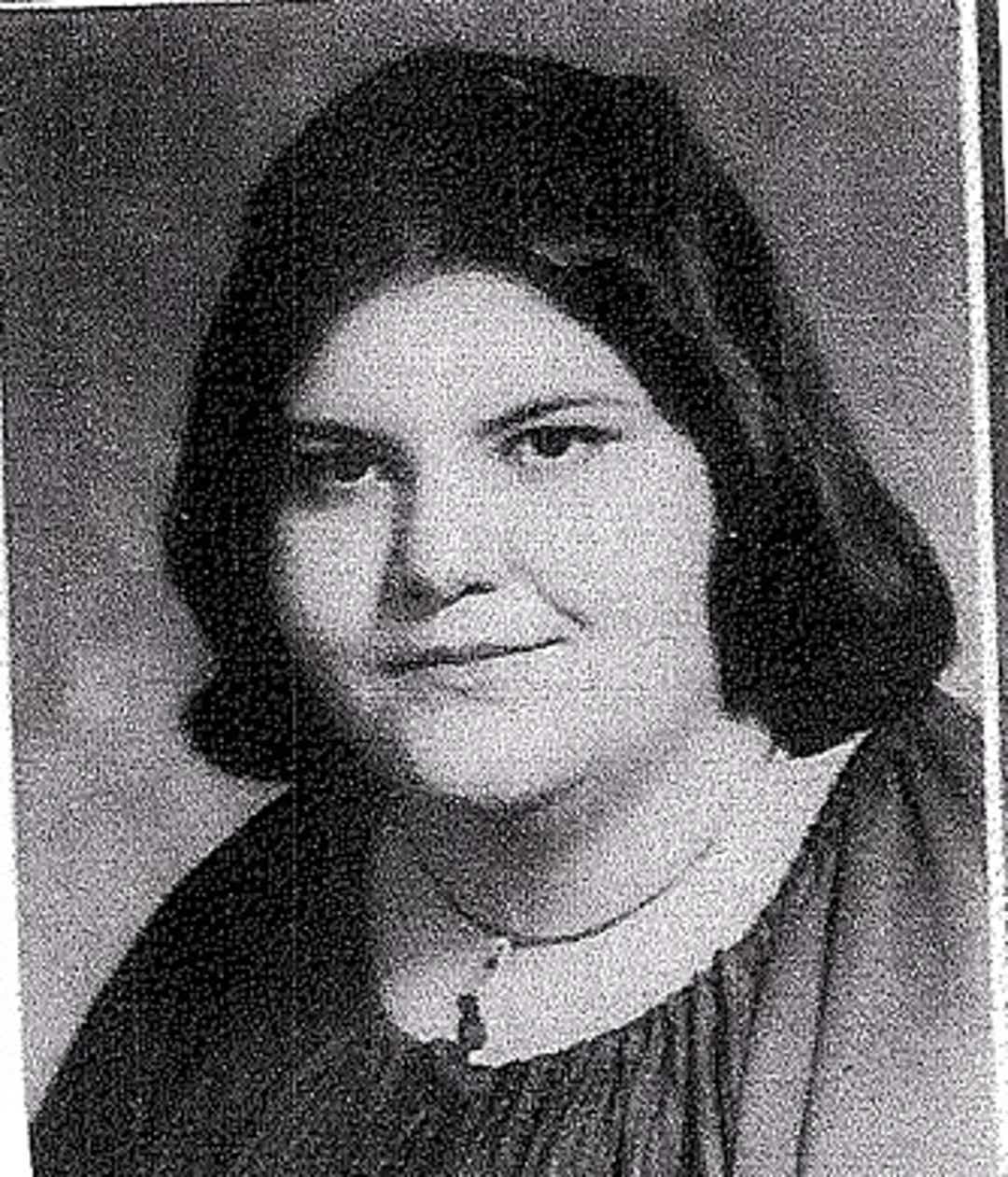

Unclaimed: Suzanne Triano changed lives. Now, her remains wait unclaimed in Pennsylvania

Jo Ciavaglia Bucks County Courier Times

Published 4:21 PM EDT Aug 27, 2020

Suzanne Triano was 21 and facing life in prison for killing her stepfather. Then a Delaware judge offered her a rare and unusual path to freedom.

Eight years later, Triano was released from prison, where she had become a counselor and an artist who created a comic book about AIDS and painted murals.

She returned to the community, the judge who sentenced joined her at speaking engagements across the state. For years, they talked about the sometimes deadly impact of family violence and childhood abuse.

Then, slowly, Triano disappeared from public view and the judge’s life.

When she died seven years ago in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, no one claimed her body.

The coroner’s office cremated her remains and poured her ashes into a plastic box. It was stacked on a metal shelf with more than 100 other forgotten dead whose remains wait in a storage room. This news organization identified Triano as part of its ongoing series on the unclaimed dead in county coroner's offices.

Triano's name lives in faded newsprint and the fading memories of a retired judge. She took a man's life, then devoted her life to teaching others how to make better life choices.

How she ended up unclaimed in a suburban Pennsylvania coroner’s office is described in spare and medically sterile language in county records:

Narrative: ER to report the death of a 50-year-old white female. The decedent was recovering at a rehabilitation hospital after surgery to open a direct airway through an incision in her trachea two months earlier. She went into cardiac arrest.

Cause of death: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease.

Date/Time of death: January 24, 2013, 03:55 a.m.

Next of Kin: [Blank]

An only child with no children of her own, Triano had severed contact with family during her incarceration.

“That’s by my choosing,” she told a Rotary Club audience in 1993. “They're in denial and it's too painful for me.”

This news organization was unsuccessful in attempts to reach other children of Caleb Maclary, the man Triano killed, through emails or phone messages. Her mother, Margaret, died in 1993 at age 65.

Never in doubt

According to his obituary, Caleb Lewis Maclary worked on the family farm in New Castle County, Delaware, most of his adult life.

He retired from the farm in the mid-1950s, and much of the land was sold to a housing developer.

Later in life, Maclary worked part time as a butcher until he retired for good in 1974 at the age of 63. By then, he had been a widower for three years.

Sometime after that, he met Triano’s mother Margaret, who was 17 years younger than him. Suzanne was her only child.

On an early Tuesday morning in May 1984, the 73-year-old Maclary was found dead on the kitchen floor of the family’s Wilmington home. He had been stabbed in the chest multiple times.

Police found the murder weapon, a thin-blade butcher knife, on a bookcase upstairs, according to a newspaper story on the murder. Maclary was buried with his first wife, Pearl, in a historic church cemetery.

Triano’s guilt was never in doubt. She was the one who called police to report the murder.

She claimed Maclary had been drinking and attacked her after she refused his orders to leave the home. They struggled and she stabbed him.

Triano was charged with first-degree murder and possession of a deadly weapon. The state later reduced the charges and she pleaded guilty to second-degree murder.

Delaware Superior Court Judge Vincent Poppiti sentenced Triano to life in prison, but he included an unusual incentive in the plea bargain deal: the possibility of parole after 11 ½ years, if Triano rehabilitated herself. She would end up serving only eight years.

At the Women’s Correctional Institute in Claymont, Triano found something she would later tell others she never before experienced: a real sense of family with unconditional love, and a nurturing and supportive environment.

Triano attended therapy, confronting a childhood where sexual abuse and physical violence was handed down from one generation to the next as far as she could remember.

In time, she made peace with her inner demons, and expressed remorse for her crime.

Triano told audiences that abuse was a way of life for her family. She claimed she did not remember a time when her stepfather did not physically abuse her mother.

“From the day she married him to the day I killed him,” she said during one public appearance, according to a 1993 newspaper story.

“I dealt with (violence) daily. It was the first thing I’d see in the morning, and the last thing before bed,” she said. “I don’t want to use that as an excuse. He did not deserve to die, not by my hand.”

Carry that forward

Triano found a new sense of purpose and community service in prison, she said.

She was among the first state inmates trained as an HIV-AIDS peer educator and outreach worker in 1989, when AIDS was still a headline-grabbing public health crisis.

She counseled fellow inmates about how to protect themselves from the often deadly disease.

In prison she created an educational comic book called "Before I Used to be Scared" to teach fellow female inmates about HIV and AIDS and how they can protect themselves.

She earned permission to do freelance artwork including logos for the Delaware Department of Corrections. She created band posters for a local bar. She designed greeting cards for a children’s rights group in San Francisco.

Art was something Triano used as an emotional outlet since childhood. Before prison, she told a reporter in 1992, her work had no feeling. But as her emotional wounds healed, it reflected in her art.

“It gets overwhelming at times," she said.

Triano wrote to Judge Poppiti telling him about her new life and thanking him for taking a chance on her. She sent him thumbnail sketches of her artwork.

“I was kind of touched to remember what she had to say about her time in prison and the fact she said, prison life saved her life,” Poppiti said in a phone interview. “She was able to provide the kind of teaching to women in her prison setting and then she was able to carry that forward.”

Poppiti was chief judge of the Delaware Family Court system in 1992 when he commissioned Triano to paint murals in the lobby and two waiting rooms at the Jean Kane Foulke du Pont Family Court building in Wilmington.

At the time, Triano was on the cusp of parole after meeting the requirements for early release. Her future plans included pursuing a degree in art therapy and working with children who were sexually abused.

She told the News Journal she was thrilled at the opportunity to repay the judge.

“He could have sent me to the state hospital. I have to admit I was state hospital material at the time,” Triano said. “If I had not been incarcerated, I would either be at (Delaware State Hospital) or I would have been dead. I truly believe that.”

The building where Triano painted those murals is no longer in use as a courthouse.

Poppiti doesn’t know if Triano’s murals are still there. This news organization was unable to confirm what happened to the murals after contacting multiple state agencies.

Raising awareness

After she was paroled in June 1992, Triano and Poppiti started appearing together at speaking engagements across the state. It was a pairing that lasted several years, Poppiti said.

At appearances, the judge shared with audiences the sketches Triano sent him when she was in prison.

“You can see the progress in her mind of what justice ultimately looks like,” Poppiti told Capital City Rotary Club members in a 1993 luncheon, according to a Delaware State News story.

At the luncheon, Triano told the audience she couldn’t change what happened to her.

“But if I can bring awareness to others, maybe we can prevent (domestic violence) from happening,” she said, according to news reports. “There is so much more I want to do. Society seems so gentle to me now.”

Their pairing was powerful and progressive for the time, Poppiti said.

”We were really at the front end, beginning to address issues involving domestic violence," he said. "She was extraordinarily well-spoken. She just oozed the kind of engaging personality she was.”

In 1993, Triano's work with AIDS education was highlighted in an issue of the National Prison Project Journal.

At the time she was working as a certified AIDS educator and outreach worker and trained foster parents who cared for HIV-positive children.

"I see a lot of changes in self-esteem because women are giving something back to others,” Triano said in the article. “I also see women becoming more responsible and engaging in less risky behavior.”

'She has saved lives'

The National Prison Project newsletter is among the last traces of Triano found online.

The public defender who handled her murder case retired years ago. Attempts to reach him were unsuccessful. Representatives for the organizations that Triano once worked or volunteered for either didn’t remember her or didn’t return messages.

Poppiti, now 74 and mostly retired, lost track of Triano many years ago. It’s something he regrets, especially after learning about her death.

“Your heart really becomes heavy that someone with the capacity for giving, and the capacity to communicate with her heart — you wonder where all that went,” he said.

Triano had a lasting impact, not only on his life, but the Delaware community that she touched with her words and artistic talent, Poppiti said.

“I believe in my heart, when you have someone like Suzanne sharing her own story and her important messages about domestic violence, she has saved lives,” he said. “I have no question about that. I expect I’ll think of her much more often in the future.”

tinyurlis.gdu.nuclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de