Chantel Tremitiere is not the kind of person who holds back.

She was never that way. She was raised by her adoptive parents – one of 15 children of different backgrounds to be adopted by William and Barbara Tremitiere – to speak up, to say what’s on your mind, to believe that your voice is important, that your experience and your beliefs are valued, that you would be heard and understood.

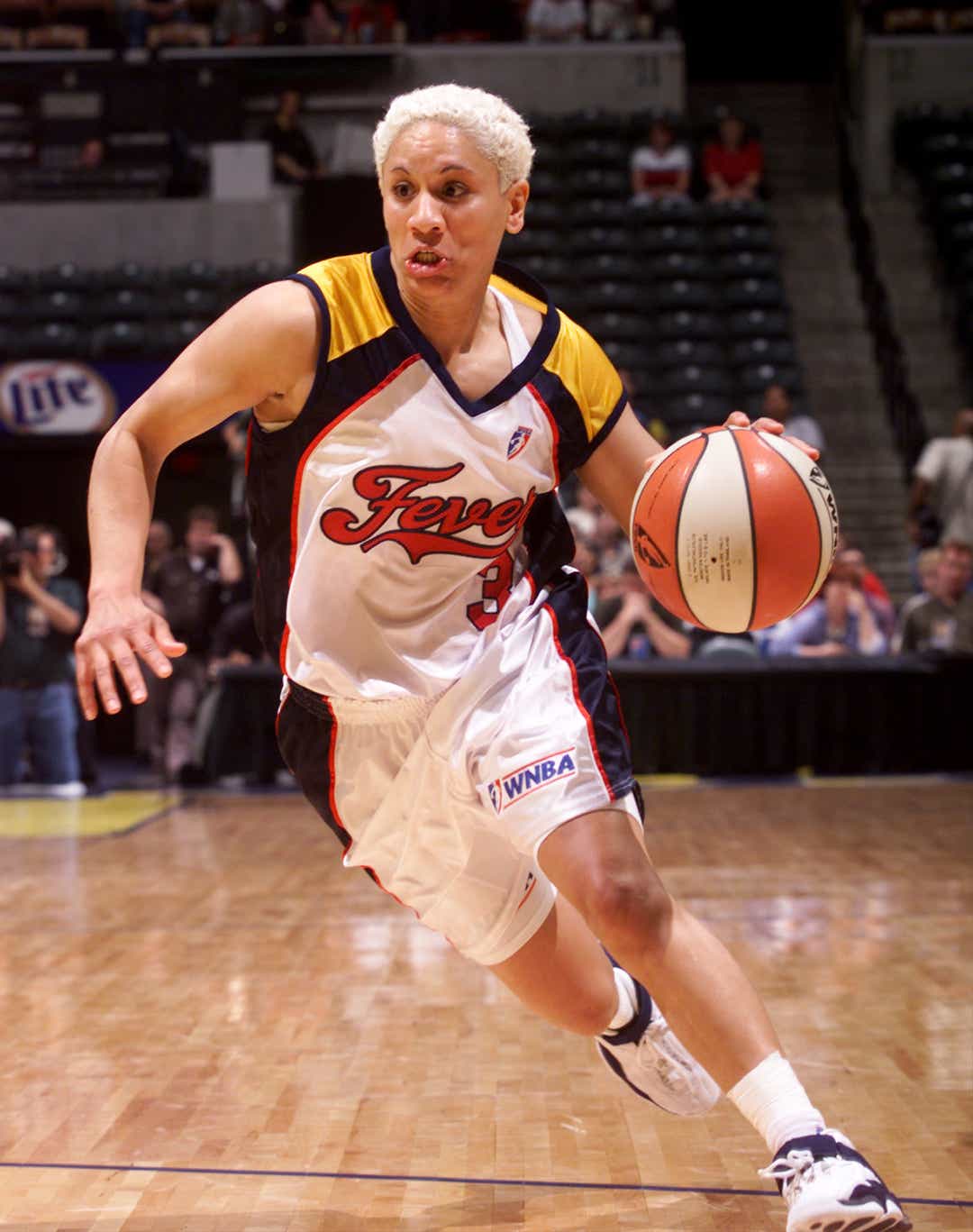

She was never that way on the basketball court. She put everything out there. As a point guard – a star in high school and college, and later, as a trailblazer in the nascent WNBA – it was about communication, about directing her team to fulfill the vision of what she saw on the court.

So, this week, she was with her fellow athletes who have stepped forward to take a stand for social justice in the wake of the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

“I think it’s long overdue,” she said. “How many African-American men have to die before changes are made?”

Sports was a means to an end

Chantel was born in Williamsport, Pa., and adopted as an infant by the Tremitieres. She was raised in a diverse household, one that placed the value of love, respect, accountability and education, above all else.

More: 'Dogs are just a part of my life': Woman rescues 175 shelter dogs, one at a time

More: 'Florida's friendliest hometown' not so friendly for anti-Trump Philadelphia transplant

She was, and is, a gifted athlete. At her hometown high school, William Penn, she was a star and earned a scholarship to Auburn University upon graduating in 1991. She was a star at Auburn, one of the country’s leading women’s basketball programs. In 1990, she was named to the NCAA All-Tournament team.

She played ball in Europe and went on to play for the Sacramento Monarchs in the WNBA – the 18th overall pick in 1997, the league’s second year, one of the founding players in the fledgling league.

Basketball, though, wasn’t the goal; it was a means to an end. After her retirement in 2002, she worked as a writer and did some acting and continued with her education — eventually, in 2017, earning her MBA and her doctorate from her alma mater. Today, she teaches in the business school at Auburn. On the website Rate My Professor, her students gush about her. “The GOAT, plain and simple,” one former student wrote. Another wrote that she is “by far the best teacher I’ve had at Auburn.” Yet another wrote, “Dr. Tremitiere is one of the few teachers where you can tell that she genuinely cares about preparing her students for their futures.”

'I'd be right there with them'

This past week, four years after Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the National Anthem to protest police brutality against African-Americans, Tremitiere watched as the NBA took a stand. It began when the players of the Milwaukee Bucks refused to take the court in the fifth game of their playoff series against the Orlando Magic. The wildcat strike spread quickly to other NBA teams and then to Tremitiere’s former league, the WNBA, and Major League Baseball. Athletes were taking a stand.

“If I were still playing, I’d be right there with them,” Tremitiere said.

She is gratified that athletes are using the platforms they have to speak out. “I’m proud of our people for speaking up and making our voices heard,” she said. If you don’t speak out, she said, “You’re part of the problem.”

To be sure, she said, this isn’t just about the shooting of Jacob Blake, of the deaths of George Floyd, or Breonna Taylor, or Ahmaud Arbery, or the lengthy list of other black people who have been killed or maimed under the cover of law and order.

It’s about 400 years of violence against African-Americans, through slavery to the lynchings to Jim Crow to the systemic racism that infects the country to this day, sometimes to lethal effect.

“For 400 years,” Tremitiere said, “every life didn’t matter. There are a lot of people who say, ‘All lives matter.’ But do they?”

'People are sick of it'

Black athletes have a long history of fighting for social justice.

Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted in 1966 and was stripped of his boxing titles, blackballed from his sport for four years of his prime. Basketball players from Bill Russell to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar spoke out for equality and civil rights at times when it adversely affected their stellar careers.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith were vilified for saluting black power on the medal stand at the 1968 Olympics. Kaepernick was unable to get a job in the NFL after taking a knee, despite the fact that he was a Super Bowl quarterback and is unquestionably more skilled than many of those who remain employed.

Something is different now.

“People are thinking that enough is enough,” Tremitiere said. “I just think people are sick of it.”

She believes, “it comes from the top,” that the racial animus emanating from the White House has infected the public discourse and created an atmosphere that condones and encourages division and hatred.

As an example, Tremitiere pointed to 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse, who is now charged with first-degree murder after opening fire on protesters in Wisconsin with a semi-automatic military-style rifle, killing two people.

“He didn’t do that on his own,” she said. “Somebody taught him that.”

'Something much deeper happening'

Tremitiere comes from a town that, in 1968 and 1969, was torn apart by racial animus, the ‘69 riots resulting in two shooting deaths, a white police officer and the daughter of a black preacher.

She fears that the current strife, left unchecked by ignoring the underlying inequities that exist in our country, could culminate in terrible and horrifying results. “A race war,” is how she describes it.

It doesn’t need to be this way, she said.

“There’s something much deeper that’s happening here,” she said, citing the inequality that seems to be baked into the American cake. “That’s what we have to start looking at. Unfortunately, I believe, the people who can make the changes we need are being the quietest. At the end of the day, I think it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

Columnist/reporter Mike Argento has been a Daily Record staffer since 1982. Reach him at 717-771-2046 or at mike@ydr.com.

tinyurlis.gdu.nuclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de

مقالات مشابه

- رژیم صهیونیستی. Wolf مشت عقب با عواقب برای شهرستان کسب و کار است که به زرد بیش از حد به زودی

- ده چیزی که درباره زمین نمی دانید

- شرکت صادرات و واردات کالاهای مختلف از جمله کاشی و سرامیک و ارائه دهنده خدمات ترانزیت و بارگیری دریایی و ریلی و ترخیص کالا برای کشورهای مختلف از جمله روسیه و کشورهای حوزه cis و سایر نقاط جهان - بازرگانی علی قانعی

- آیا استخر بادی در منازل کوچک نصب میشود؟

- یک راه جدید برای جشن 7-یازده روز

- Easy, healthy snacks to power you through your online semester

- راه متحده منطقه خلیج ولز فارگو ایجاد اجاره صندوق کمک

- مسلم حقوق ؟

- شرکت صادرات و واردات کالاهای مختلف از جمله کاشی و سرامیک و ارائه دهنده خدمات ترانزیت و بارگیری دریایی و ریلی و ترخیص کالا برای کشورهای مختلف از جمله روسیه و کشورهای حوزه cis و سایر نقاط جهان - بازرگانی علی قانعی

- 5 تازه کار اسباب بازی اشتباهات احتمالاً میتوانید رفع در حال حاضر